Jewish Request at the End of WWII: Let My People Go [to Palestine]!

(13 May 1945)

Source: Palestine Post, May 14, 1945, pp. 1 and 3; See abbreviated version of the speech in Daphne Trevor, Under the White Paper: Some Aspects of British Administration in Palestine from 1939 to 1947, Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Press Ltd, 1948, p. 131.

“In view of the staggering proportions of our catastrophe, let us not belittle the miracle of our deliverance. The designs of the enemy to make the world ‘Judenrein’ (‘Jew-clean’) stand defeated. Let us remember the countries which stood on the brink of the precipice —one such country was England, another was Palestine. Time after time we were threatened. Let us never forget the days of El Alamein when the beginnings of our achievements and the hope of generations of Jewish people wavered between life and death and the Yishuv of 600,000 souls were confronted by the abyss of oblivion

“Is there any other people throughout the world which draws up such a balance sheet or tasted the bitter fare of death as we did? Others were menaced by conquest and enslavement; in our case alone an entire people seemed destined to perish. At a time when other peoples count their battle casualties in hundreds of thousands; we count millions slaughtered as sheep. Against the background of this overwhelming demonstration of shame and dishonor of our weakness, every manifestation of strength and valor in Jewry, the memory of every death in battle, is doubly precious. [Shertok extolled all Jews fallen in the present war, beginning] the Ghetto heroes, the fallen Palestinian volunteers, those killed in the Libyan campaign, or during commando operations in East Africa, the Aegean islands, the Adriatic, those drowned at seam and civilian volunteers, who laid down their lives in daring operations on the Syrian coast and in the Syrian desert, and who met death behind enemy lines to rescue Jews, or help the Allies, and lastly the Jewish Brigade casualties. All these deaths upon the battlefield were a consolation to downtrodden, humiliated Jewry.

They stood as a symbol that Jews can live and die differently.

This must be the last war in which the fate of the Jewish people hangs in the balance, the last time that Jews become objects of pity and consideration. The Jewish people must free itself from the humiliation of fear. It is entitled to ask the world to assist it to achieve freedom from fear and want. Will the Allied world with whom we fought shoulder to shoulder whose loyal prop we were in this whole part of the world would help us get that freedom or would abandon us to our fate? If we are abandoned, we shall continue our struggle alone, spurning shallow counsels or false compromises. It was brought to a victorious conclusion because at a certain stage somebody was not deterred from carrying on the struggle alone. But before we reach that last resort, we appeal to all to help us rescue our brothers and ourselves. Is it all that a Jew is entitled to – not be slaughtered? A call should go out in the first instance to those who in London hold the keys of entry to the gates of Palestine. They should open them widely. [Shertok then chided Sir Anthony Eden’s remark in San Francisco several days earlier that Britain had carried out its obligations to the Jews, and quoted a denunciation of the White Paper made in the House of Commons in May 1939 by Mr. Churchill. “There is a breach. There is a violation of a pledge. There is an abandonment of the Balfour Declaration. There is the end of a vision, a hope, a dream.”]

And we should likewise go out to all from Moscow to Paris who hold the keys to exits […] : Let my people go. It is a great thing to be able to proclaim from Mount Scopus overlooking our holy city that Israel lives on. Blessed be the arms to which we owe our survival. Blessed be England who stood alone for a whole year when all seemed lost. Blessed be her allies. But it is not enough that we should reiterate to England and her allies that ancient call, ‘Let my people go’ – what the world must know is that Israel has decided to live differently. Israel claims its country back, not to displace others but to re-settle and develop, not to subjugate others but to deliver herself.

We claim freedom of immigration and settlement, freedom to defend ourselves, to be masters of our destiny, to establish friendship with our neighbors based on mutual respect and common interest. We claim equality and statehood.”

[1] “People’s Call from Mt. Scopus Mr. Shertok’s Keynote: “Let My People Go”” Palestine Post [Jerusalem] 14 May 1945: 1+. Historical Jewish Press. The National Library of Israel. Web. 28 June 2012. <http://www.jpress.org.il/

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Abdulrahman ‘Azzam Pasha Rejects Any Compromise with Zionists

(September 1947)

David Horowitz, State in the Making, New York: Alfred Knopf, 1953, pp. 233-235.

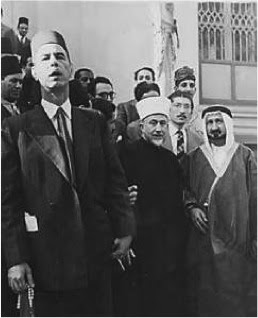

Figure 1 Azzam Pasha (L), alongside Mufti Haj Amin El-Husseini (C) in Cairo, c. 1948 (Public Domain, Egypt)

In the 1930s, Zionist leaders at times approached Arabs living in Palestine seeking a dialogue on how to perhaps narrow the nationalist differences between the two communities. David Ben- Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency at various times, had discussions with members of the Nashashibi family in Jerusalem, Awni Abd al-Hadi, a staunch Palestinian nationalist, and in the 1940s with Musa al-Alami. In the 1940s as well, just after the publication of the August 1947 United Nations Special Committee Report on Palestine, which called for Arab and Jewish states in Palestine, an international regime for Jerusalem and an economic union between the two proposed states, Zionists continued their dialogue with Arab leaders in surrounding states. They had discussions with Emir Abdullah of Jordan, various Syrian Arab leaders, and in September 1947 with the noted Egyptian nationalist ‘Azzam Pasha, who was the first Secretary General of the Arab League (1945-1952). The three members of the Jewish Agency who met with ‘Azzam Pasha were Aubrey (Abba) Eban, Jon Kimche, and David Horowitz, all worked for the Jewish Agency in Palestine. They met with him at the Savoy Hotel in London, on September 16, 1947. Horowitz’s account of that meeting revealed ‘Azzam Pasha’s total rejection of a Jewish State, his suggestion that violence would be the only recourse, and his speculation that Palestine might be lost to Arab control. The Zionist’s efforts at building a dialogue with Palestinian or Arab League leader were unsuccessful in terms of either duration or substance. ’Azzam Pasha’s thoroughly antagonistic view of Zionism is found in this description of that meeting.

– Ken Stein, May 2011

Figure 2 David Horowitz, who recalled his meeting with ‘Azzam Pasha prior to the partition of Palestine (United Jewish World Press, PERMISSION PENDING)

He [Jon Kimche] phoned one morning, out of a clear sky, and said it was possible to arrange an interview with Abdul Rahman Azzam Pasha, leader and secretary-general of the Arab League. I at once agreed, and an appointment was made for five o’clock the following afternoon.

Aubrey, Jon Kimche and I went to the Savoy Hotel, where Azzam Pasha was staying, and a short while later were sitting with a swarthy, lean-faced Arab with dark piercing eyes, who received us with great courtesy.

I opened the conversation. After setting out my view of UNSCOP’s report, I turned to analyze the situation: “The Jews are a fait accompli in the Middle East. Sooner or later the Arabs will have to reconcile themselves to the fact and accept it. You Arabs cannot wipe out or exterminate over a half a million people. We, for our part, are genuinely desirous of an agreement with the Arabs and are prepared to make sacrifices for one.

“Such an agreement will be reached in time, so why precede it by squabbling, fighting and bloodshed? There are no conflicting fundamental interests and insuperable obstacles involved in any agreement. We’re not hankering after expansion, conquest, or domination of other peoples. We want to become integrated in the fabric of the Middle East so that we can be mutually beneficial.

“We know that it’s a vital interest for us. I understand that you don’t wish to rely on assurances and lofty sentiments. Consequently, we’re ready to propose a concrete plan for co-ordination of interests and a real peace between the two peoples.

“The plan is in three parts:

“First, political: that is, an arrangement with the Arab League based on a system of well-defined rights and obligations.

Aubrey, Jon Kimche and I went to the Savoy Hotel, where Azzam Pasha was staying, and a short while later were sitting with a swarthy, lean-faced Arab with dark piercing eyes, who received us with great courtesy.

I opened the conversation. After setting out my view of UNSCOP’s report, I turned to analyze the situation: “The Jews are a fait accompli in the Middle East. Sooner or later the Arabs will have to reconcile themselves to the fact and accept it. You Arabs cannot wipe out or exterminate over a half a million people. We, for our part, are genuinely desirous of an agreement with the Arabs and are prepared to make sacrifices for one.

“Such an agreement will be reached in time, so why precede it by squabbling, fighting and bloodshed? There are no conflicting fundamental interests and insuperable obstacles involved in any agreement. We’re not hankering after expansion, conquest, or domination of other peoples. We want to become integrated in the fabric of the Middle East so that we can be mutually beneficial.

“We know that it’s a vital interest for us. I understand that you don’t wish to rely on assurances and lofty sentiments. Consequently, we’re ready to propose a concrete plan for co-ordination of interests and a real peace between the two peoples.

“The plan is in three parts:

“First, political: that is, an arrangement with the Arab League based on a system of well-defined rights and obligations.

Figure 3 Abba Eban, who later served in the Knesset and as Foreign Minister of Israel, was also present at the meeting. (Public Domain, Israel)

“Secondly, security, which will have the effect of dissipating your groundless suspicions of our alleged expansionist ambitions, though we keep on declaring and repeating that our sole object is to in-gather the hundreds of thousands of our brethren within the bounds prescribed for us to revive the wilderness, and despite the fact that any attempt on our part to break out of this frame will be met with the opposition of the entire world. We’re ready to give you concrete guarantees, both from ourselves and from the United Nations.

“Finally, the plan will have an economic section to be drawn up in consultation between the parties and will deal with the conjoint development of the Middle East, to the advantage and prosperity of the Arab masses.”

Azzam Pasha: “The Arab world is not in a compromising mood. It’s likely, Mr. Horowitz, that your plan is rational and logical, but the fate of nations is not decided by rational logic. Nations never concede; they fight. You won’t get anything by peaceful means or compromise. You can, perhaps, get something, but only by the force of arms. We shall try to defeat you. I’m not sure we’ll succeed, but we’ll try. We were able to drive out the Crusaders, but on the other hand we lost Spain and Persia. It may be that we shall lose Palestine. But it’s too late to talk of peaceful solutions.”

Aubrey Eban: “The UNSCOP report establishes the possibility of a satisfactory compromise. Why shouldn’t we at least make an effort to reach an agreement on those lines? At all events, our proposal is a first draft only and we shall welcome any counterproposal from your side”

Azzam Pasha: “An agreement will only be acceptable at our terms. The Arab world regards you as invaders and is ready to fight you. The conflict of interests among nations is, for the most part, not amenable to any settlement except armed clash”

Horowitz: “Then you believe in the force of arms alone? You don’t think there has been any progress whatsoever in the settlement of controversial issues among different peoples?”

Azzam Pasha: “It’s in the nature of peoples to aspire to expansion and fight for what they think is vital. It’s possible I don’t represent, in the full sense of the word, the new spirit that animates my people. My young son, who yearns to fight, undoubtedly represents it better than I do. He no longer believes in us of the older generation.

When he came back from one of the more violent student demonstrations against the British, I told him that in my opinion the British would evacuate Egypt without the need for his demonstrations. He asked me in surprise: ‘But, Father, are you really so pro-British?’

“The forces which motivate people are not subject to our control. They’re objective forces. It may have been possible in the past to have reached agreement if there’d been amalgamation from below. But it’s no longer feasible. You speak of the Middle East. We don’t recognize that conception. We only think in terms of the Arab world. Nationalism, that’s a greater force than any that drives us. We don’t need economic development with your assistance. We have only one test, the test of strength. If I were a Zionist leader, I might have behaved the way you’re doing. You have no alternative. In all events, the problem now is only soluble by the force of arms.”

Azzam Pasha’s forcefulness and fanaticism impressed us deeply. His world-outlook had something of the biological determinism of racial theory. The realistic picture he painted was a fatalistic one of objective, almost blind forces erupting and spilling over unchecked on the stage of history.

Azzam proclaimed his attachment to democratic principles in our ensuing conversation, it was true, but his extreme beliefs bordered on a fascist world-conception. The admiration of force and violence which was evident in his statements seemed to us both strange and repugnant, and his description of any attempt at compromise or peace as a naïve illusion left no door of hope open.

In spite of the amiable, even cordial atmosphere, we felt the full historic impact of this dramatic encounter. With it vanished the last effort to bridge the gulf. The final illusion of reaching an agreed and peaceful solution had been exploded.

We left the hotel and crossed over into the Strand both stirred and depressed. Azzam had managed to impart something of his spirit and outlook to us. We saw looming up before us latent, powerful forces pushing us irresistibly and inescapably toward the brink of a sanguinary war, the outcome of which none could prophesy.”

“Finally, the plan will have an economic section to be drawn up in consultation between the parties and will deal with the conjoint development of the Middle East, to the advantage and prosperity of the Arab masses.”

Azzam Pasha: “The Arab world is not in a compromising mood. It’s likely, Mr. Horowitz, that your plan is rational and logical, but the fate of nations is not decided by rational logic. Nations never concede; they fight. You won’t get anything by peaceful means or compromise. You can, perhaps, get something, but only by the force of arms. We shall try to defeat you. I’m not sure we’ll succeed, but we’ll try. We were able to drive out the Crusaders, but on the other hand we lost Spain and Persia. It may be that we shall lose Palestine. But it’s too late to talk of peaceful solutions.”

Aubrey Eban: “The UNSCOP report establishes the possibility of a satisfactory compromise. Why shouldn’t we at least make an effort to reach an agreement on those lines? At all events, our proposal is a first draft only and we shall welcome any counterproposal from your side”

Azzam Pasha: “An agreement will only be acceptable at our terms. The Arab world regards you as invaders and is ready to fight you. The conflict of interests among nations is, for the most part, not amenable to any settlement except armed clash”

Horowitz: “Then you believe in the force of arms alone? You don’t think there has been any progress whatsoever in the settlement of controversial issues among different peoples?”

Azzam Pasha: “It’s in the nature of peoples to aspire to expansion and fight for what they think is vital. It’s possible I don’t represent, in the full sense of the word, the new spirit that animates my people. My young son, who yearns to fight, undoubtedly represents it better than I do. He no longer believes in us of the older generation.

When he came back from one of the more violent student demonstrations against the British, I told him that in my opinion the British would evacuate Egypt without the need for his demonstrations. He asked me in surprise: ‘But, Father, are you really so pro-British?’

“The forces which motivate people are not subject to our control. They’re objective forces. It may have been possible in the past to have reached agreement if there’d been amalgamation from below. But it’s no longer feasible. You speak of the Middle East. We don’t recognize that conception. We only think in terms of the Arab world. Nationalism, that’s a greater force than any that drives us. We don’t need economic development with your assistance. We have only one test, the test of strength. If I were a Zionist leader, I might have behaved the way you’re doing. You have no alternative. In all events, the problem now is only soluble by the force of arms.”

Azzam Pasha’s forcefulness and fanaticism impressed us deeply. His world-outlook had something of the biological determinism of racial theory. The realistic picture he painted was a fatalistic one of objective, almost blind forces erupting and spilling over unchecked on the stage of history.

Azzam proclaimed his attachment to democratic principles in our ensuing conversation, it was true, but his extreme beliefs bordered on a fascist world-conception. The admiration of force and violence which was evident in his statements seemed to us both strange and repugnant, and his description of any attempt at compromise or peace as a naïve illusion left no door of hope open.

In spite of the amiable, even cordial atmosphere, we felt the full historic impact of this dramatic encounter. With it vanished the last effort to bridge the gulf. The final illusion of reaching an agreed and peaceful solution had been exploded.

We left the hotel and crossed over into the Strand both stirred and depressed. Azzam had managed to impart something of his spirit and outlook to us. We saw looming up before us latent, powerful forces pushing us irresistibly and inescapably toward the brink of a sanguinary war, the outcome of which none could prophesy.”

Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husayni Decision to Reject the 1939 White Paper

(March 1939)

Al-Husayni, Hajj Amin. “The Decision by Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husayni to reject the 1939 White Paper.” Izzat Tannous, The Palestinians Eyewitness History of Palestine. New York: Igt Co, 1988. 309-310. Print.

Figure 1 (L) Dr. Izzat Tannous, then a student at St. George’s University in Jerusalem, c. 1913. (PERMISSIONS PENDING!, Institute for Palestine Studies, Photographic Collection).

Dr. Izzat Tannous, an Arab Christian, headed the Arab Center in London, an organization formed to promote support for the Palestinian Arabs. In 1936, he was a supporter of the Mufti and a member of an Arab delegation to London. Palestinian Arab delegations went to London half a dozen times between 1920 and 1936 to protest the British policy of supporting the development of the Jewish National Home and to urge Palestinian Arab self-determination. According to British Colonial Secretary Malcolm MacDonald, Tannous “tended to be a moderate, therefore his influence in Palestine was not very great…he [was] a man capable of reason and some courage…whatever influence he may have had would be exerted on the side of peace.”

Tannous, like many of his Palestinian peers, vigorously opposed Zionism and the development of the Jewish national home; specifically, he opposed the British policy of promoting the 1937 partition of Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states. In 1938, the British withdrew the partition idea as quickly as they had introduced it in the 1937 Peel Commission Report: it was deemed unworkable primarily because the Arab state would not have been viable and Arab leaders in surrounding states were clamoring for partition to be still-born. In its new policy statement on Palestine released in early 1939, Britain proposed to severely limit Jewish immigration and land purchase, and to establish a unitary state in Palestine that would come about within a decade. In such a state the Arab population would have become a majority and the Jews a minority. Tannous and all members of the Arab Higher Committee were in favor of accepting such a solution. The only dissenting and apparently important voice was that of Hajj Amin al Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem. The Mufti had enormous power in his hands, yet he chose non- engagement with the British. Furthermore, he chose not to take any political path that might sometime in the future compromise total and absolute Palestinian Arab control over all of Palestine. He did not want to consider sharing any present or future political power with any other Arab leader in Palestine, and he steadfastly opposed any Jewish presence in Palestine, even with minority status. For the Mufti, there simply was no place for the Jews or Zionists in Palestine. For the Palestinian Arabs, 1939 was a moment when active British policy and Arab state support for Palestinian national aspirations was at its peak. In the late 1930s, in the 1940s, and particularly from 1945-1948, British political leadership and the American State Department, especially the Near East section, vigorously opposed or sought to delay Palestine’s partition, which would have seen the creation of a Jewish state. Yet again, in this nine year period, as in 1939, Palestinian and Arab leadership chose emphatically not to engage in political discussions to secure either a federal state dominated by the Arab population, or a two state solution. Arab leaders consistently wanted an absolute guarantee that the Zionists would have no influence in determining Palestine’s future. As for those ‘moderates’ who wanted to consider a compromise with the British in 1939, they simply did not want to stand up in public against the Mufti of Jerusalem.[1]

Below, Tannous recollects the Mufti’s spring 1939 decision to reject the federal state solution, going against fourteen other Palestinian notables who favored the federal state solution idea. For more information, see Malcolm MacDonald’s “Discussion on Palestine” (August 21, 1938), which holds considerable detail of Tannous’s meetings with MacDonald in August 1938. See British Cabinet Papers 190 (1938) and Great Britain, Foreign Office 371/21863.

-Ken Stein, January 2012

The Arab Higher Committee and the White Paper

Figure 2 Members of the Arab Higher Committee. Front row from left to right: Ragheb Bey Nashashibi, chairman of the Defence Party, Haj Amin eff. el-Husseini, Grand Mufti & president of the Committee, Ahmed Hilmi Pasha, Gen. Manager of the Jerusalem Arab Bank, Abdul Latif Bey Es-Salah, chairman of the Arab National Party, Mr. Alfred Roke, influential land-owner. c. 1936 (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collection, no known restrictions).

“As soon as the White Paper was published, the members of the A.H.C. (Arab Higher Committee) and all those Palestinians who attended the Palestine Conference in London gathered at Haj Ameen’s residence near Jouneh, the suburb of Beirut. The two Defense Party members, Ragheb Nashashibi and Yacoub Ferraj, were absent because they had resigned from the A.H.C. in 1937.

The Committee met every day and the White Paper was scrutinized in detail. We were fifteen in number. The Committee met for nearly three weeks. They were day-long meetings, only broken by generous luncheons served at Haj Ameen’s table.

The discussion was in a family like manner at first, sitting in a circle and all taking part. The morale was high and the expectation for a brighter future was higher. This went on for a time, dreaming of a Palestinian Arab as the head of a department, as a Minister or a Prime Minister or even at Government House, and why not? But this sweet dream did not last long. The discussion became more strained as some of us began to realize that Haj Ameen was not in favor of accepting the White Paper. This negative stand, which gradually became more pronounced, made the atmosphere extremely tense, The arguments between Haj Ameen and the rest of the members became acute and after a fortnight of discussion it became quite clear that the only person who was against accepting the White Paper was Haj Ameen Al-Husseini. The remaining fourteen members were not only strongly in its favor, but were determined to put an end to the negative policy Arab leadership had been adopting heretofore. “Take and demand the rest” was now their new motto. If there were excuses for our negative stands in the past, and there were, they were gone.

At this stage of the discussion, an atmosphere of resentment and dismay prevailed over the meetings and there was reason for it. The fourteen members knew very well that the acquiescence of Haj Ameen Al-Husseini was a very essential requisite and that without his blessing because of his magic influence on the Palestinian masses, the White Paper would not be implemented, a goal which the Zionists were madly seeking to score. Consequently, the sole concern of the Committee was now concentrated on convincing Haj Ameen that his negative stand was extremely detrimental to the Arab cause and was serving unintentionally, the Zionist cause,; and that he was doing exactly what the Zionists wanted him to do.

Figure 3 the Mufti of Jerusalem exiting the offices of the Palestine Royal Commission in Jerusalem, c. 1937 (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions).

It is true that none of us could claim that the White Paper was a perfect political instrument without blemish; but at the same time; none of us could deny that it effected drastic changes in the despotic policy which had, so far, governed Palestine and that it had marked a decisive turning point in the history of Palestine. The fourteen members felt that they could not possibly discard a policy which had put an end to the Jewish National Home policy in Palestine; nor could they conscientiously refuse a policy which had cancelled the establishment of a Zionist State recommended by the Royal Commission and adopted by the British Government. And what right do we have to: discard a policy which stipulated that:

After the elapse of five years and the contemplated 75,000 immigrants have been admitted, H.M.G. will not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under obligation to facilitate further development of the Jewish ‘National Home by immigration.

Did not this statement put an end to the development of the Jewish National Home and an end to the Balfour Declaration? And what gain do we, the Arabs of Palestine, expect to procure from discarding such a policy.

Another week of heated argumentation took place within the Committee with no tangible result. Haj Ameen kept repeating his arguments that the White Paper contained too many loopholes and ambiguities to be of any benefit; the “transitional period of ten years” was too long and the “special status of the Jewish National Home was too much of an ambiguity to be accepted. There were other objections he raised which space will not permit me to record; but, all in all, they were not important enough to permit the total discard of policy which gives us our major demands, put an end to our fears for the future and which our enemies simply crave to abolish!”

[1] Issa Khalaf, Politics in Palestine Arab Factionalism and Social Disintegration, 1939-1948, Albany, 1991, pp. 74-77.

No comments:

Post a Comment